Attraction

Recreation

The photo was immediately recognized as an innovative step in the development of art. Central Asia and, in particular, Turkistan, had perfect conditions for the quick progression of photographic art. The unique nature and picturesque images of its people - everything which seemed exotic to the Europeans, was fixed on photographic plates. Photographers gladly agreed to carry the bulky photographic gear and fragile glass plates from afar to satisfy their great interest in this region and to record it for history.

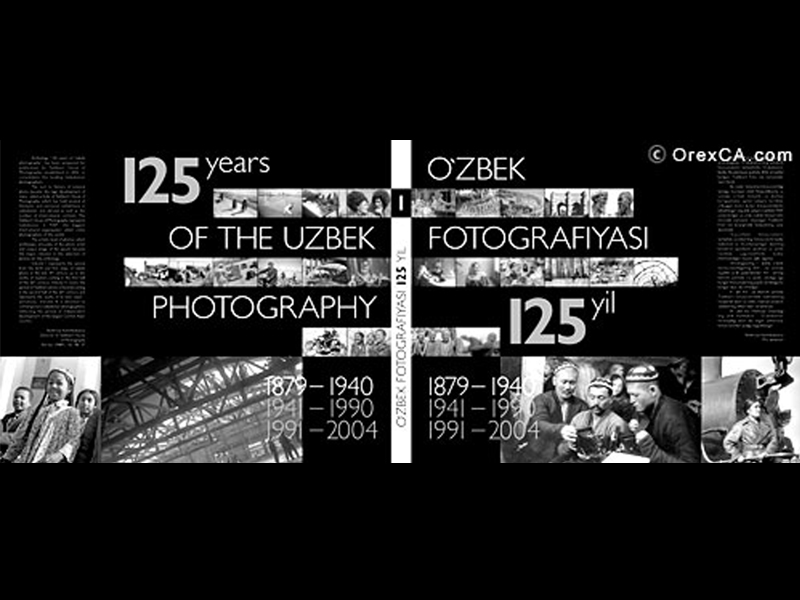

The unhurried life in the East resonated with the lethargy and, possibly, the forced idiosyncrasies of photo taking in that period. The still moments and frozen frames waited far ahead and actually were not so important. In fact, the first photos, taken 125 years ago, are valuable as they give us a lucky chance to see the depth of that life instead of fixing its worldliness. These pictures bring the past closer to us and expose details which could not be preserved in any other way. It was a joyous time for the photo. Its creative component wonderfully combined with the mass character of the Uzbeks. It doesn't compare to the present, but in any case was able to survive the stormy 20th century, considering the fact that only 10-20 percent of human products avoid decay and destruction.

The photo, like the other achievements of the growing industrial epoch, not only recorded reality. It actively participated in life. The photo became more accessible to the people than painting and graphic portraits.

The opportunities of photo portraits were unprecedented in the East, where there existed native traditions and approaches to portraying the human image. Invaluable samples of old photo portraits, created more than a century ago, sit before us. The photo made the person see himself and his life more significantly. Look at how great is the dignity on the first photo portraits. The first photographers in Uzbekistan were Europeans, who brought Western European cameras. The local people were gradually captured by the growing interest in the technical innovation. Some of them overcame dissidence and became photographers and owners of the first photo studios. The first photos made on the territory of today's Uzbekistan date to the end of the 1870s. The date of Hudaibergen Divanov's birth - 1879 - symbolically coincides with the birth of the Uzbek photo.

The name of this remarkable person, the first domestic photographer and cameraman, entered the history of the Uzbek photo.

Much in the life of Hudaibergen Divanov reminds one of a legend. It forms a chain of surprising events, full of deep meaning.

A short introduction cannot cover all aspects of this subject, but the question of how the relations between the outstanding invention of the 19th century and Hudaibergen occurred and developed is worthy to be widely known.

Everything was predetermined. About two hundred Germans were moved from the Russian Volga region to Khorezm, kishlak of Ok Maschit (White mosque). Among them was the inquisitive craftsman, Penner. The local people revised his name into Panorbuva - grandfather-lantern, probably because he brought a very strange subject reminding a lantern - it was the camera "Zot". It chanced that Hudaibergen, the clever son of Nurmuhammad, who was the office secretary at Khiva khan Muhammad Rakhim II, saw the camera. Soon the boy became the friend of Panorbuva and showed the great interest in photo taking. The old German gave him both the camera and all required accessories. From 1903, Hudaibergen started to take photos of Khiva minarets piercing the blue cloudless sky, his friends and relatives.

Everything was predetermined. About two hundred Germans were moved from the Russian Volga region to Khorezm, kishlak of Ok Maschit (White mosque). Among them was an inquisitive craftsman named Penner. The local people revised his name into Panorbuva - grandfather-lantern, probably because he brought a very strange object reminiscent of a lantern - it was a "Zot"camera. It was by chance that Hudaibergen, the clever son of Nurmuhammad, who was the office secretary of Khiva khan Muhammad Rakhim II, saw the camera. Soon the boy became friends with Panorbuva and showed a great interest in photography. The old German gave him both the camera and all the required accessories. From 1903, Hudaibergen started to take photos of Khiva minarets piercing the blue cloudless sky, and his friends and relatives. However, his growing fame brought problems to the first Khorezm photographer - the adherents of religious law and their leader, judge Salim Akhun, complained to the khan that his son was occupied with activities not approved by God. The father of Hudaibergen was reminded that to draw, and furthermore to take human photos, was a sin, as angels would not enter a room adorned with human portraits. Nurmuhammad-aka, who was ready to spend all his salary to educate his only son, answered that if angels really would refuse to visit the room where his son had photos; the other nine rooms of his house would be for him free range. The khan, being a poet and educated person, asked Hudaibergen to photograph him. The governor liked the photo and estimated the creative and technical skills of the young artist. He not only protected him from the clergy, but invited him to work at the mint. In 1907, a delegation of the Khiva khan, led by Right Vizier Islam Khodja, went to Saint Petersburg. Hudaibergen, already titled as Divanov, was brought along to memorialize this event. He was permitted to stay in the Russian capital for two months in order to study photographic art.

Hudaibergen bought a "Pate"cinematograph, gramophone, and new cameras from Petersburg.

Looking at H. Divanov's photos, we are amazed at the historicism of his art. He quickly realized his high mission as the representative of his people and his epoch, responsible to future generations. When choosing his subjects, he directed the camera at things which obviously bore the features of eternal value - minarets, mosques and historical places. Photographing people, he aspired to combine the ethnographic approach with the aesthetic - each character, representing this or that type, self-expressed as a unique individual. Fate intervened in the other human joys and even deprived him of that which is most important - his son and daughter died as children. He had only wife, his faithful companion and … his passion for the photo and cinema.

The high post of the Minister of Finance of the Khorezm Republic, the director of the photo club of the Pedagogical Technical College, the honoured work as the first Uzbek cameraman at the first Uzbek film studio - all this is part of his biography. When H. Divanov was young, he was a member of the Mladokhivians' party, which finally cost him his life: being a retiree, H. Divanov was repressed by the Soviet authorities as a cohort of Akmal Ikramov and Faizulla Khodjaev. In 1940, he was shot. In 1958 H. Divanov was exonorated.

Information on the majority of Uzbekistan photographers of the late 19th - first third of the 20th centuries is very poor or completely absent. This is quite typical of a situation where the photo was recognized exclusively as a documentary source. Paradoxically, this relative anonymity promoted some freedom in the field of photo art.

In the Soviet period, many Uzbekistan photographers took socially ordered shots and showed themselves as original photo artists, choosing expressive camera angles and giving such expressive play of light and shadow, that even prosy objects (bridges, factories, buildings, etc.) obtained self-sufficiency as artistic images.

Among photographers of that period was Samarkand photographer P. Kildyushev, Tashkent press photographer M. Penson, Fedorov, who created the photo-annals of Chirchikstroy, and a few others. P. Kildyushev's works demonstrated the influence of the classic Western-European and Russian fine arts - carefully verified composition, and central linear and light-and-shadow perspective, which softly draw our attention to psychological features of the photo portraits.

On the contrary, a decorative effect and modernistic expression prevail in the works of Fedorov and some other photographers of the 1930s-40s. The unexpected foreshortenings put forward the details of machines and industrial structures, and the light and shadow express the extreme tension of the changes running in life.

M. Penson's photos were probably the most accordant with that epoch and aesthetic. The social and reportage features were accented, and were partly balanced by some universal aesthetics - * classic composition quite often combined with the informative aggressiveness of the social order and laconic figurativeness of details. Sometimes all that turned into the aesthetics of placards and slogans.

The relatively weakened canons of perception and their east-western mixture caused a high tolerance of art styles and directions. That greatly promoted the blossoming of photo art in Uzbekistan. Some photographers continued and developed these realistic traditions, describing the exotic reality. Some of them focused on form-making and were surprised, finding out that the decorative effects could suddenly be reminiscent of the masterpieces of local carpet weaving and other applied arts and crafts, for centuries selecting the elements and compositions which have recently been discovered by the European avant-garde. Some of them have synthesized all that, mixing genres and styles, unexpectedly quickly in this eternal and slow land, and not thinking of how they brought their own contribution into the creation of this new human-made eternity.

A full survey of the photo art of Uzbekistan, developed over three centuries, awaits and still hides many discoveries, both informative and aesthetic. Photos from private collections, mass photos from numerous cards, and many others remained beyond this album, for various reasons. The first approach naturally is wide and represents an attempt to cover the phenomenon in general, drawing on public and scientific interest. The original photo art of Uzbekistan is worthy of being carefully studied.